Desk review on breast cancer

Preface

This desk review titled ‘Breast Cancer – the disease: causes, consequences, treatment and stigma’ is issued by Share-Net Bangladesh secretariat and is funded by Share-Net International in the Netherlands. It was written by Gazi Sakir Mohammad Pritom, Rushdia Ahmed and Ashfique Rizwan at the Center for Gender, Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (CGSRHR) at BRAC James P Grant School of Public Health (BRAC JPGSPH), BRAC University. Share-Net Bangladesh is a platform for the Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) practitioners in Bangladesh and assist to share and exchange information, tools and knowledge within the Community of Practice (CoP) in SRHR. Share-Net started its journey in Bangladesh from 2015. It is a unique partnership between Red Orange Media and Communications, a media and communication company, and the CGSRHR, at BRAC JPGSPH. This partnership has enabled Share-Net Bangladesh to foster an environment where practitioners are updated with latest developments in SRHR in Bangladesh. BRAC JPGSPH and Red Orange jointly led the platform from October 2014 to December 2017. Since 2018, Red Orange has been hosting Share-Net Bangladesh and BRAC JPGSPH is providing technical expertise on SRHR to the platform. Share-Net Bangladesh has been playing a pioneering role in starting decisive discussions on various critical issues with the members.

This review aims to give a comprehensive idea on the status of Breast Cancer in Bangladesh and to provide an overall picture of the situation and some recommendations for the policymakers.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the contribution of Tanha Tabassum Nunna for gathering data and helping with writing some section in the first draft of the report. We also acknowledge our reviewers Nazrana Khaled and Prof. Sabina Faiz Rashid from CGSRHR of BRAC JPGSPH for their critical inputs on this desk review.

Acronyms

| BCPS | Bangladesh College of Physicians and Surgeons |

| BSE | Breast Self-Examination |

| CBE | Clinical Breast Examination |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CHW | Community Health Worker |

| DDT | Dichloro Diphenyl Trichloroethane |

| DALY | Disability-Adjusted Life Year |

| IARC | International Agency for Research on Cancer |

| PCB | Poly Chlorinated Biphenyl |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| NCCN | National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

| NHS | National Health Service |

| NICRH | National Institute of Cancer Research and Hospital |

| USA | United States of America |

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer-related mortality in women worldwide (World Health Organisation, 2018). In 2018, it is estimated that 627,000 women died of this disease around the globe (World Health Organisation, 2018). According to World Health Organization (WHO), 2.1 million women around the globe are affected by breast cancer every year (World Health Organisation, 2018). Even though the developed countries faced increased number of breast cancer cases earlier, in recent years the trend is extending to both developed and developing countries simultaneously (World Health Organization, 2018).

According to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the USA, breast cancer is an abnormal growth of breast cells in which they grow out of control. There are many types of breast cancer, depending on the cells they contract such as either the cells of ducts or in lobules in the breast.

Any of these types of breast cancer can start in the breast but later, can spread to other parts of the body (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018).

This desk review draws on available literature on this topic and is structured in the following sequence:

- The current prevalence of breast cancer in Bangladesh and other developed & developing countries,

- Underlying reasons of breast cancer,

- The physical and mental consequences of breast cancer and its impact on one’s sense of self-identity, gender, body and desirability,

- The healthcare, screening and treatment of breast cancer in developed and developing countries and in Bangladesh,

- Finally, perceptions of stigma and misconceptions around breast cancer in developed and developing countries and in Bangladesh.

METHODS

The methodology was informed by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [Moher et al., 2009]. We searched PubMed database till December 31, 2018 to identify relevant literatures. A list of keywords such as Breast Cancer, Public Health Stigma, Psychosocial concerns, traditional healers, formal and informal providers etc. were identified and used for search during January 2019 by two researchers. The search strategy used was: (Breast Cancer AND Public Health AND Bangladesh, Breast Cancer AND Stigma AND Bangladesh, Breast Cancer AND Stigma AND South Asia, Breast Cancer AND Stigma AND “Developing countries”, Breast Cancer AND Stigma AND “Developed countries”, (Breast Cancer) AND “Psychosocial Concerns”, (Breast Cancer) AND “Traditional Healers”, (((breast cancer in south asia) AND Breast Cancer[Title])) AND (Bangladesh[Title] OR India[Title] OR Pakistan[Title] OR Sri lanka[Title] OR Maldives[Title] OR Afghanistan[Title] OR Myanmar[Title] OR Nepal[Title] OR Bhutan[Title] OR Indonesia[Title] OR Thailand[Title] OR Malaysia[Title] OR Vietnam[Title] OR Cambodia[Title] OR Lao[Title] OR Singapore[Title] OR China[Title] OR Taiwan[Title])). Studies of any design were eligible to be included in this review given they investigated the prevalence and trends of breast cancer disease in Bangladesh, different countries in South Asia and Africa, and developed parts of the world; explored the causes and consequences of breast cancer in Bangladesh or globally; described the treatment and screening facilities nationally and internationally; were published in a peer-reviewed journal or identified via the reference lists of included articles; and were written in English.

A total of 213 records were identified using this search strategy in PubMed. After screening through titles and abstracts of the identified 213 literatures and reading through the full texts, 132 were further excluded on the basis of exclusion criteria set. The exclusion criteria were,

1. Studies which are focused on laboratory research of breast cancer e.g. studies on gene expression or new chemotherapy trails in lab, which discuss technical and biomedical aspects of breast cancer. 2. Clinical trials which recruit only women of one ethnicity other than South Asian (e.g. only Caucasians, only Africans etc.) in its study population. Finally, 81 relevant peer reviewed articles were included for qualitative synthesis for this desk review exploring areas of current prevalence; underlying reasons; stigma and misconceptions; physical and mental consequences; healthcare, screening and treatment of breast cancer globally and in Bangladesh.

We also reviewed 5 websites for breast cancer related information and statistics. These were World Health Organisation (WHO), International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), Center for Disease Control (CDC), National Health Service (NHS) and BREASTCANCER.ORG. These websites are well established and were selected purposively for inclusion in this desk review.

SECTION I – PREVALENCE OF BREAST CANCER: GLOBAL AND BANGLADESH

Globally, the most common cancer for women is breast cancer: 2.4 million cases were identified from 1990 till 2015, through a systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study. Breast cancer is also figured as the leading cause of cancer-related deaths and Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) for women with estimates of 523 000 deaths and 15.1 million DALYs (Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration et al., 2017). In fact, it is one of the top ten causes of death among high income countries worldwide (World Health Organization, 2018).

Table 1 – Top 25 countries with highest prevalence of breast cancer in the world

Source: Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global Cancer Statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin, in press. The online GLOBOCAN 2018 database is accessible at http://gco.iarc.fr/, as part of IARC’s Global Cancer Observatory.

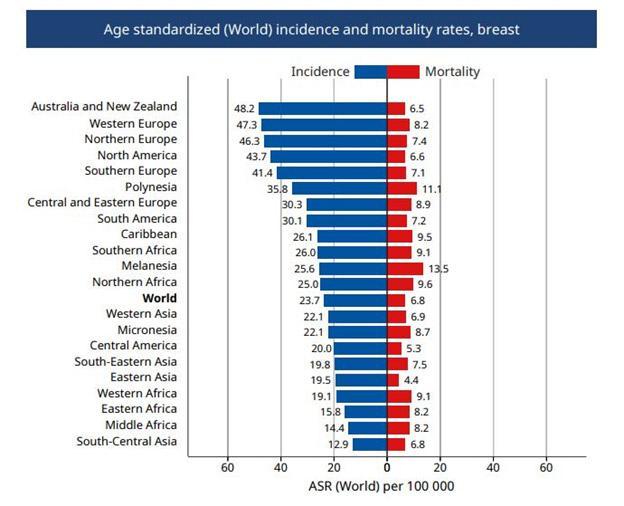

From the table above, it is evident that the prevalence of breast cancer is highest in developed countries such as in Europe and North America. However, the difference in mortality rates among different regions show a contrasting picture. A fact sheet published by International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC: part of WHO) shows that although the higher income regions have high incidence of such cases, they face lower mortality from breast cancer compared to their lower-and middle-income counterparts:

The graph above indicates that Australia and New Zealand has higher incidence rates (48.2 per 100,000 population) compared to South-Eastern Asia (19.8 per 100,000 population). However, the mortality rates are less in Australia and New Zealand (6.5 per 100,000 population) compared to South-Eastern Asia (7.5 per 100,000 population) (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2018a). Similar scenario of higher mortalities and lower incidences is evident for other Asian and African parts of the world compared to the West.

Incidence of breast cancer is shown to vary due to ethnicity. A study conducted in England utilized cancer registration data from 357,476 patients between 2001-2007. The study explored the difference of cancer incidence among different ethnicities. South Asians were found to have lower rates of breast, ovarian and cervical cancer compared to the Caucasian population. They also concluded that Bangladeshis residing in England had the lowest rates of all cancers among the South Asian population (Shirley, Barnes, Sayeed, Finlayson, & Ali, 2014).

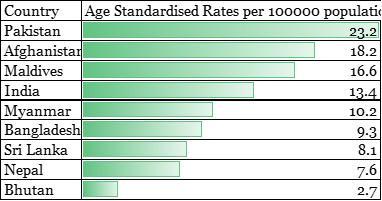

The latest incidence estimates for South Asian countries can be seen from Figure 2. It shows that the highest incidence of breast cancer is in Pakistan among other South Asian countries followed by Afghanistan, Maldives, India and Myanmar. Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal and Bhutan are the bottom four in that list (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2018b).

Figure 2 – Age Standardized Rates for countries in South East Asia (expressed in per 100000 population)

Source: Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global Cancer Statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin, in press. The online GLOBOCAN 2018 database is accessible at http://gco.iarc.fr/, as part of IARC’s Global Cancer Observatory.

In Bangladesh, no national prevalence data on breast cancer has been investigated till now. Few studies have found that breast cancer is the most common cancer for women in Bangladesh (Ahmed, Asaduzzaman, Bashar, Hossain, & Bhuiyan, 2015; Hossain, Ferdous, & Karim-Kos, 2014; Hussain & Sullivan, 2013; Story et al., 2012). According the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) under WHO, the number of cases of breast cancer in Bangladesh was 12,764 in 2018 (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2018). This estimation also suggests that 6,846 women have died of breast cancer in Bangladesh in the same year (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2018). National Institute of Cancer Research and Hospital (NICRH) in Bangladesh reported 5,255 cancer cases during the period of 2005-2010; among which, the mean age of patients was 41.8 years (Hossain, Ferdous, & Karim-Kos, 2014). Another study conducted in Dhaka, the capital city of Bangladesh, in 2010 with 1300 patients admitted to Delta Medical College found that breast cancer accounted for 99.6% of all cancers among women and 22.4% for both sexes (only 1 case in 400 men was diagnosed as breast cancer) (Parveen, Rahman, Sultana, & Habib, 2015).

SECTION II – BREAST CANCER: BIOMEDICAL AND NON-BIOMEDICAL FACTORS

Cancer causation is poorly understood till today. The basic anomaly is a damage to the DNA which can lead to abnormal cell growth. This section outlines the risk factors causing breast cancer such as the biomedical and non-biomedical factors along with various environmental and lifestyle related components.

1. Biomedical factors

WHO sums up a number of known biomedical risk factors that are identified for breast cancer causation from several biomedical research studies conducted in the USA and UK (WHO, 2014).

Genetic Mutations

Among various risk factors, heredity or a familial history of breast cancer (which can be due to a mutation in the genes BRCA1, BRCA2 or p53) is the most recognized one (Howlader et al., 2017; Kuchenbaecker et al., 2017; WHO, 2014). Most of the studies carried out on the genetic causes of breast cancer have been carried out in the developed countries. As a result, very few studies are available in the context of South-Asia. Few studies have been conducted in India on the genetic mutations linked with breast cancer. A study conducted between 1999 to 2003, with 204 patients from Safdarjung Hospital, New Delhi and LLRM Medical College, Meerut, identified different variants of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic mutations among the patients of breast cancer (Saxena et al., 2006). However, a study conducted in Sri Lanka found no significant association with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation and breast cancer among the population studied (57 breast cancer patients, 25 at risk individuals and 23 healthy individuals) (De Silva, Tennekoon, Karunanayake, Amarasinghe, & Angunawela, 2014). Due to few available studies in the context of South-Asia and Bangladesh, WHO established (using comprehensive review from literature body till 2014) causal factor of genetic mutation in the genes BRCA1, BRCA2 or p53 is considered as a risk factor of breast cancer in these countries as well. In Bangladesh, similarly a case-control study done with 310 adult women with invasive breast cancer and 250 age matched women as controls, recruited from 5 tertiary hospitals in Dhaka, found that mutation in BRCA1, BRCA2 and HER2 genes are responsible for breast cancer in the studied population (Parvin et al., 2017). Other genetic mutations such as Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 2 (FGFR2) have also been found in Indian population (Siddiqui et al., 2014) but studies have not explored it in other South Asian population. A hospital-based case control study, recruiting 852 women from the department of surgical oncology AIIMS, India found that FGFR2 can increase the risk of breast cancer among the study participants (Siddiqui et al., 2014).

Exposure to estrogen

Biomedical factors such as prolonged exposure to endogenous or exogenous estrogens are described to increase the risk of inducing breast cancer (WHO, 2014). Endogenous estrogen exposure is increased through early menarche or late menopause that increases the length of reproductive period, hence, increasing the chance of contracting breast cancer. On the other hand, exogenous estrogen exposure occurs when estrogen is introduced to the body by use of oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy (Ark, Lemons, Aul, & Oss, 2001; Million Women Study Collaborators, 2005; Kelsey, Gammon, & John, 1993; Pike, Spicer, & Dahmoush, 1993; Schairer et al., 2000). In Bangladesh, a hospital-based case-control study conducted between January 2007 and December 2010 among 129 age matched pairs, similarly linked early age of menarche (endogenous estrogen exposure) with increased risk of breast cancer (Iqbal et al., 2015). Another descriptive case-control study with 160 Bangladeshi participants (equal cases and controls) has found hormone therapy, positive family history, early menarche, late menopause and abortion to be the primary risk factors for breast cancer among the study population (Ahmed et al., 2015). Exposure to estrogen has been hence found to be a risk factor for Bangladeshi population alongside the developed countries.

Human Mammary Tumour

Laboratory studies in New York, USA have also shown that human mammary tumor virus can be linked with breast cancer causation (Yue Wang et al., 1995). Only one study has been found in South Asia which looked at the association between human mammary tumor and breast cancer. A study with 58 breast cancer patients in Myanmar has identified presence of human mammary tumor in breast cancer patients, which may indicate an association (San et al., 2017). However, to establish a causal linkage, more research needs to be carried out.

Alongside these biomedical factors that play a role in breast cancer causation, several non-biomedical factors are also responsible in the development of the disease.

2. Non-biomedical factors & Breast Cancer

Non-biomedical factors causing breast cancer include various environmental factors and lifestyle related factors around the disease. There are also factors that play protective roles for breast cancer disease.

Environmental factors

Environmental factors contribute to a greater extent in increasing the risk of breast cancer. A 2010 review article on association of environmental factors causing breast cancer published in the journal Medicina sheds light on this issue. The article details on factors such as organochlorines (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane or DDTs, polychlorinated biphenyl or PCBs), exposure to heavy metals (cadmium, copper, cobalt, nickel, lead, mercury, tin, and chromium), ionizing radiation, solar radiation and electromagnetic fields acting as risk for breast cancer causation (Strumylaitė, Mechonošina, & Tamašauskas, 2010). Similarly in Bangladesh, exposure to chemicals such as DDT was discussed as a possible cause to develop breast cancer. By consuming dried fish ‘shutki’, a very popular dish among the Bangladeshi population, people are exposed to DDT without their knowledge and become vulnerable to develop breast cancer as the preparation process of this food item included usage of DDT (Hussain & Sullivan, 2013). There have been, however, no study looking at the causal relationship between exposure to heavy metals and development of breast cancer in the context of Bangladesh.

Lifestyle related factors

Additionally, life style related factors are found to be associated with developing breast cancer. A study conducted with global secondary data from Comparative Risk Assessment project (including both developed and developing countries), found that alcohol use, being overweight or obese and physical inactivity can be risk factors for breast cancer. The study concluded that among high income countries, the most important factor was overweight and obesity while in low-and-middle-income countries, it was physical inactivity (Danaei, Vander Hoorn, Lopez, Murray, & Ezzati, 2005). In 2002–2005, a case–control study conducted in Tamil Nadu in India with 1866 cases and 1873 controls established association between obesity (increased waist size >85 cm, large body size at age 10 and increased BMI) and breast cancer (Mathew et al., 2008). In Bangladesh, a case control study conducted in 3 urban hospitals and one rural community site from January 2007 to December 2010 similarly found the risk of breast cancer to be increasing with increased body mass index (≥25 kg/m2), indicating to the link of breast cancer and obesity (Iqbal et al., 2015).

Protective factors

A few studies found some factors which can be protective against breast cancer. A desk review of all published literature till 2007 concluded that physical activity was found to significantly reduce risk of breast cancer by 25%-30% in women from both developed and developing countries (Friedenreich & Cust, 2008). Sunlight exposure has also been established as protective against breast cancer. A study conducted among agriculture workers in Iowa, USA with data between 1993 to 2004, found that sun exposure may be associated with reduced risk of breast cancer (Engel et al., 2014). In a population-based study in 2010 among women aged between 35 and 45 years in Hong Kong, researchers looked at the association to sunlight exposure with breast density (assessed by Tabár’s mammographic pattern) to understand the risk of breast cancer development. The results showed that higher sunlight exposure was protective for increased breast density (Wu et al., 2013). This in turn meant that sunlight exposure was protective for breast cancer since previous meta-analysis studies have identified breast density to be markers of possessing breast cancer (Mccormack, Dos, & Silva, 2006).

SECTION III – HEALTHCARE AND TREATMENT OF BREAST CANCER: GLOBAL AND BANGLADESH

Early diagnosis of breast cancer increases the chance of seeking suitable treatment option earlier, thus, enhancing the possibility of survival. This section gives a generic review of screening and treatment of breast cancer starting with the WHO guidelines on screening and moving to screening guidelines from the American Cancer Society. The section also lays out different treatment guidelines and focuses on the screening and treatment condition in the context of Bangladesh.

Screening for breast cancer

Breast cancer is one of the cancers which can be effectively screened with established screening protocols (Lauby-Secretan et al., 2015). In order to detect early and better prognosis, it is critical to have screening facilities for breast cancer in place. A review published in 2009 that looked at screening programs established for at least 10 years in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom concluded that breast cancer screening by mammography among women aged more than 50 years can reduce mortality by 25–30% (Schopper & de Wolf, 2009). The available screening technologies for breast cancer include digital mammography, digital breast tomosynthesis, breast ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and clinical breast examination (Fiorica, 2016). The 15th volume of “Handbook of Cancer Prevention” from IARC, WHO also lists other techniques of screening such as: electrical impedance imaging, molecular breast imaging and positron emission mammography which are still not mainstreamed given the high cost and technical complexities involved as well as the lack of substantial evidence in different settings for these screening methods (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2016). Studies have looked at the cost effectiveness of screening procedures (mostly mammography and some on clinical breast examination) using databases such as global burden of diseases, Dutch screening trials, Observational trial data from USA, Sweden, Netherlands, India and found that screening for breast cancer among women aged between 40-70 years irrespective of the setting (developed or developing), can be cost-effective as well as can improve rates of early detection and offer better treatment options for patients (de Koning et al., 1991; Ginsberg, Lauer, Zelle, Baeten, & Baltussen, 2012; Mushlin & Fintor, 1992; Okonkwo, Draisma, der Kinderen, Brown, & de Koning, 2008; Tosteson et al., 2008; Van Der Maas et al., 1989).

For countries with resource constraints and weak health systems, it is important to devise screening facilities alongside the developed countries as WHO 2018 report identified high risk of breast cancer non-detection till late stage in low resource settings (World Health Organisation, 2018). The WHO position paper on mammography screening published in 2014, recommends screening by mammography and clinical breast examination according to resource availability and status of health system in each setting. The WHO guideline states that for 40-49 years old women, in well resource settings, a population-based screening with mammography is justified, but for low resource settings, such population-based screening is not recommended considering the resource constraints and lower risk at this age-group. For women aged 50-69 years, WHO recommendation is divided in three scenarios . For women in well resource settings, WHO strongly recommends population-based screening with mammography and for low resource and strong health system settings, the recommendation of mammography is conditional . For low resource and weak health system settings, such screening is not recommended and clinical breast examination is recommended instead (World Health Organisation, 2014).

Similar to the WHO guideline for well resource countries, the American Cancer Society gives strong recommendation for mammography screening of average risk women (those who do not have a positive genetic mutation, have had a positive family history of breast cancer or have had radiotherapy to the chest at a young age) starting from age 45. They also suggest qualified recommendation for annual screening of women between 45 and 54-years age. For women above 55 years, the organization recommends having biennial screening with mammogram. The guideline does not recommend clinical breast examination due to lack of strong evidence supporting such procedure (Oeffinger et al., 2015).

As discussed above, the WHO guidelines recommend clinical breast examination for countries with lower resource setting and weak health systems (which are lower and middle income countries). This is applicable to Bangladesh too as the country has been grouped as lower and middle income country i.e. lower resource setting and weak health systems by WHO classification. Countries in the South Asian regions including Bangladesh should follow the WHO guideline if they have not developed a guideline of their own backed up by strong evidence. There have been researches that prove the utility of such screening in the South Asian setting. For example, a cluster randomised controlled trial in India in 2006 tested the utility of a triennial clinical breast examination screening in reducing mortality and morbidity. The study concluded that the procedure has a sensitivity of 51.7% and specificity of 94.3% (Sankaranarayanan et al., 2011). However, Bangladesh has no established population-based screening program for the early detection of breast cancer and cancer screening is mostly encouraged by breast self-examination and mammography at a personal level. According to a literature review published in Cancer Epidemiology in 2014, nearly all cases of breast cancer in Bangladesh are detected clinically (i.e. by physicians) due to a lack of organized population-based screening program (Hossain et al., 2014). A multi-country research (which included Bangladesh) conducted among female university students, has informed that the proportion of monthly breast self-examination is below 2% in Bangladesh (Pengpid & Peltzer, 2014). There has been some evidence suggesting different factors (e.g. education) can improve screening awareness. In a cross-sectional quantitative study conducted among 152 women who were employees at different level in 10 different universities of Dhaka, Bangladesh, it was found that education was significantly associated with the knowledge of breast screening; both Breast Self-Exam and Mammography procedures (Rasu, Rianon, Shahidullah, Faisel, & Selwyn, 2011). The study found that women with higher educational levels were 6 times more likely to know about breast examination and 3 times more likely to know about mammograms compared to those with lower educational levels. In this urban setting, about half of the study participants did not perceive any barriers to getting a mammogram done and 86% had willingness to pay for the procedure (Rasu, Rianon, Shahidullah, Faisel, & Selwyn, 2011). However, knowing about screening and the practice of screening is not reciprocal as it has been shown in the same study. The study by Rasu et al. (2011) also found that majority of participants (from the capital city of the country) knew about breast cancer screening (mammogram 79% and breast self-examination 86%) and yet less than a fifth of all women interviewed ever had a mammogram done.

Studies have also hinted as to why the knowledge does not translate into practice. A recently published nationally representative cross-sectional survey in Bangladesh conducted in 7 districts from 7 divisions in the country with 1590 women found that 90% of the women never underwent clinical evaluation or mammography screening because they assumed it is recommended only for women with symptoms (Islam, Bell, Billah, Hossain, & Davis, 2016). No knowledge of screening (40.1%), anticipated expenses for screening (7.2%), modesty issues (4.7%) and religious barriers (1.7) were also reported by them as reasons for not undergoing screening (Islam, Bell, Billah, Hossain, & Davis, 2016). It is hence important to educate people for regular screening even when there is no symptoms or breast anomalies since this perception can clearly impede early detection and treatment of breast cancer in this population.

To encourage screening of breast cancer among women, community health workers (CHWs) may play a role, due to their proven effectiveness in previous health related interventions (child immunization, ORS etc) in Bangladesh (Perry et al., 2017). A study conducted in Khulna, rural Bangladesh with 3,147 women above 18 years age, tested the feasibility to of breast cancer case finding by the help of CHWs. The study found that among the rural women, only a small proportion (1% cases) was unwilling to undergo screening i.e. refused clinical breast examination (Chowdhury et al., 2015), even though it required no direct costing like screening by mammography does. Also, one could argue in contrast, CHWs are seen as local level informal providers and might not be given similar importance as such the physicians, whose advice and treatment might be taken more seriously by patients. On the other hand, e–health based interventions have been shown to effectively increase screening uptake in women with breast cancer. One study looking at an e-health intervention on breast cancer in Bangladesh found that less than 1% of respondents declined participation in screening by clinical breast examination (Ginsburg et al., 2014). Researchers had postulated in the past that breast health awareness programs in Bangladesh are likely to be ineffective due to “entrenched complex socio-cultural, economic, and health systems barriers that include gender inequity and human rights issues” (Story, Love, Salim, Roberto, Krieger, & Ginsburg, 2012). However, a later study concluded that rather than cultural and religious barriers, lack of understanding of the importance of screening and assessing asymptomatic women impediment breast cancer screening in Bangladesh (Islam, 2016).

Treatment of breast cancer

Treatment of breast cancer is dependent on the stages of cancer progression that are Stages I-III and Stage IV or Metastatic, Lobular Carcinoma in Situ, and Ductal Carcinoma in Situ . In this section, we discuss different treatment guidelines in the developed countries and also focus on the current condition and guidelines for breast cancer treatment in Bangladesh.

Depending on the stage and grade of cancer, the American Cancer Society lists Surgery, Radiation, Chemotherapy, Hormone Therapy, Biological Therapy or a combination of two or more therapies as treatment options for breast cancer (American Cancer Society, 2017). In the latest updated treatment guidelines of National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) (version 3.2018) in the USA, treatment of cancer has been proposed as surgery followed by radiation and/or chemotherapy in combination with adjuvant therapies, according to staging and grading of cancer along with individual physiological conditions (National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2018). The American guideline very much focuses on the aspect of physical treatment of cancer and does not look to treat the mental health aspect of breast cancer. The psychological distress is recommended to be assessed only in case of young patients for whom mastectomy can have consequences. Newer methods of mastectomy, such as nipple sparing mastectomy has been shown to improve American patients’ quality of life while maintaining oncological safety standards (Tokin, Weiss, Wang-Rodriguez, & Blair, 2012). Recent advances in surgery has also allowed for further development of the technique and robotic surgeries are now being used for improving precision. For example a case report from Korea stated improved precision and decreased distress in patients with gasless robot-assisted nipple-sparing mastectomy (Park et al., 2018).

Care and support is critical for cancer care. A number of studies identify other therapies that help women cope with breast cancer such as exercise, social support from peer groups or networks, psycho-educational programs etc. The National Health System (NHS) in the UK adds psychological help as a vital treatment option alongside those mentioned in the American guideline to be successful in the treatment plan (NHS, 2016). In Canada, cancer care also addresses the mental aspect of the patient; also offering other support and care options if one is not inclined to receive cancer treatment. The 5-year survival rate after treatment in Canada is 88% (Canadian Cancer Society, 2012), which is close to its neighbor in the south 90% (American Society of Clinical Oncology, 2019). A 1997 study conducted with 46 women with early stage breast cancer undergoing radiation therapy in the US, showed that exercise can help with physical function as well as fatigue, anxiety and difficulty in sleeping (Mock et al., 1997). Social support (e.g. number of friends, social network and supportive persons etc.) has been shown to be effective to significantly improve breast cancer survivability as shown by a study conducted in 1981-1985 with a cohort of 133 women in Canada (Waxler-Morrison, Hislop, Mears, & Kan, 1991). A study conducted in Korea with 48 breast cancer survivors suggests that 12 week psychoeducational program such as individual face-to-face education using a participant handbook, telephone-delivered health coaching sessions can increase the quality of life and reduce psychosocial distress of Breast cancer survivors (J.-H. Park, Bae, Jung, & Kim, 2012).

In Bangladesh, cancer care has not advanced such as other specialized care facilities (i.e. care for coronary artery diseases, kidney diseases) in the country. According to a newspaper report in the Daily Star from January 11, 2019, Bangladesh has no established cancer care protocol. Bangladeshi cancer patients are currently treated in accordance with NCCN guidelines originally developed for patients in the United States (Chandan, 2019). The implications of not having a national protocol may not be apparent at the outset. However, it makes room for errors in cancer treatment and makes the patients vulnerable to chances of maltreatment. It also means that complaints in cases of maltreatment or mal-praxis cannot be established by the patients. The shortcoming of cancer care is not restricted to absence of guideline only. There is also a lack of trained professionals for cancer treatment. Concurrently, cultural and social factors make it important that the woman can access a female doctor for screening and treatment for breast cancer, a disease that is mostly suffered by women, given the barriers of shame and modesty in the context of Bangladesh. The availability of female physicians with expertise in cancer or breast cancer in particular, is remarkably low as identified from the Fellows’ registry of the Bangladesh College of Physicians and Surgeons (BCPS). A study by Ahmad et al. (2017) concluded that Bangladeshi women’s likelihood of seeking breast care was associated with the need of a female physician who could be consulted regularly (family physician), among other factors. Given the sensitivity and cultural cognition of breast as a sexual organ, it is understandable that women in Bangladesh would not be comfortable to be examined or treated by a health professional of the opposite gender.

SECTION IV – CONSEQUENCES OF BREAST CANCER

This section summarizes the range of consequences related to breast cancer on individuals such as physical morbidities, metastasis, emotional and mental impact as well as one’s sense of self-identity, gender and their bodies.

a. Morbidity related to breast cancer

Breast cancer affects physical wellbeing of the patients. A qualitative study with 34 breast cancer patients in 2008 conducted in Australia reported that they face fatigue, insomnia, numbness, pain, lymphoedema (which is the accumulation of water in the lymphatic system, suggested by swelling of limbs) and malnourishment along with the disease (Beatty, Oxlad, Koczwara, & Wade, 2008). The study also found that patients perceived a combined effect of loss of appetite, mouth ulcers and change in taste as causes behind becoming malnourished during treatment and recovery of breast cancer (Beatty, Oxlad, Koczwara, & Wade, 2008). Additionally, a case-control study in 1997 done among 864 breast cancer survivors in the USA found that physical symptoms like joint pains, headache and hot flashes were more common among breast cancer patients than in normal healthy women (Ganz, Rowland, Desmond, Meyerowitz, & Wyatt, 1998). Another cohort study initiated in 1997 with 577 women at the time of diagnosis to 6 years after diagnosis of breast cancer in the USA, revealed that majority of breast cancer patients reported poorer physical health following breast cancer that includes having frequent amenorrhea and treatment induced menopause. The patients perceived that these were induced by the cancer treatment and felt that their health condition was worse than actually it was in real (Ganz, Greendale, Petersen, Kahn, & Bower, 2003). Studies that looked at the physical effects produced due to breast cancer and/or its treatment were scarce in the context of South Asia as well as Bangladesh. Only one study was found which looked at the symptoms of breast cancer in Bangladesh. The retrospective study conducted with case reports of 120 women seeking care in a palliative care center in the only medical university in Bangladesh found the predominant consequences are pain, lymphedema, weakness and anxiety following breast cancer and its treatment (Khan, Ahmad, & Biswas, 2018).

Metastasis is another common morbidity in breast cancer patients which can cause secondary physical symptoms. Breastcancer.org, a USA based non-profit organization working to create breast cancer awareness worldwide, lists the symptoms of breast cancer metastasis on their website. Depending on the organ it invades, metastasis can cause pain or loss of function in the affected organ. For example, if ribs, lungs and liver are cancer affected, chest or abdominal pain occurs in the patients. Similarly, for the brain, headache is a common symptom. Again, metastasis of lungs can effect lung function and be manifested as shortness of breath and persistent cough; metastasis of liver can cause weight loss and fatigue; metastasis of brain can cause non-function of different parts of brain and result in loss of vision, speech or memory (Weiss, Wojciechowski, & Gupta, 2018). These can all be devastating for the affected person, both physically as well as mentally. Other studies have also linked different manifestations of the central nervous system by metastatic breast cancer (Koopman et al., ; Lin, Bellon, & Winer, 2004). Metastatic breast cancer has been linked to a range of physical problems including pain, stress and sleep disturbance in a longitudinal study in the USA with 99 women suffering from breast cancer (Palesh et al., 2007). Bangladesh, having lower resource capacity (World Health Organization, 2018) to screening procedures and treatment options, patients often face metastasis that may remain undiagnosed (The Daily Star, 2019). In addition, there are other contributing factors to metastasis in Bangladesh such as absence of coordination among various levels of healthcare providers. In an interview to the Daily Star on January 11, 2019, Professor Zafor Md Masud, head of the department of oncology, Bangladesh Medical College Hospital, explained the case of a patient who was diagnosed with breast cancer and underwent mastectomy following diagnosis. She also received chemotherapy following the surgery but neither the surgeon nor the oncologist identified a lung metastasis which had already occurred before mastectomy was performed. Professor Masud identified the absence of coordination between providers which is very common in the country and has subsequently failed to create an environment for quality treatment for breast cancer patients (The Daily Star, 2019).

b. Emotional and Mental Health conditions (Depression and Trauma)

Fear, worry and denial were reported as the immediate responses to breast cancer by a 2004 USA based qualitative study with 102 breast cancer survivors of different ethnicities. The respondents mentioned worry about children and burden to the family, concerns related to health, causes and management of breast cancer, marital and relational issues, financial and work challenges, body image and sexual health related concerns altogether affected their psychological health to a great extent (Ashing-Giwa et al., 2004). A study in the Nineties conducted in USA among 93 women undergoing cancer treatment (mastectomy or breast sparing surgery) found similar psychological distress among both treatment groups. Fatigue and emotional distress were also found to be persistent among the sample population (Hoskins, 1997). Another study conducted in 770 rural woman from Kansas, USA suggested that fear of recurrence and body shape change (i.e. loss of breast and weight-loss) can be primary psychosocial concerns of breast cancer survivors (Befort & Klemp, 2011). These studies from the USA go on to show the emotional and mental stress related to family and relationships that is brought on by the discovery of breast cancer for a patient. Similar to the USA, a study in Australia in 2008 with 34 patients of breast cancer found that during treatment, experience of isolation, depression, helplessness and loss of control were commonly noted across participants from all groups (Beatty, Oxlad, Koczwara, & Wade, 2008). Australian women reported changes in social roles, and inability to continue their level of involvement in activities including work, volunteering and sport (Beatty, Oxlad, Koczwara, & Wade, 2008). Upon treatment completion, Australian women reported feeling intensification of isolation- with many feeling abandoned by their medical team, families and reporting withdrawal of social support from friends (Beatty, Oxlad, Koczwara, & Wade, 2008). A Young Survival Coalition Research Think Tank Meeting in 2015 titled “Women: Research Priorities” highlighted the impact of breast cancer among young women. The participants at the meeting stressed the distinctive pattern of age-related challenges among young women with breast cancer including maintaining a career, child rearing, sexuality and body image, socio-economic concerns and relationships with partners, friends and family members (Korde et al., 2015). The concerns related to responsibility and relationship that were identified by women from developed countries hold true for their Asian counterparts as well. A study conducted in 2013 with 208 female breast cancer patients from a hospital in Maharashtra, India found that quality of life (QOL) scores were low among the study participants in both psychological health and relationship (Gangane, Khairkar, Hurtig, & San Sebastián, 2017). Similarly in Bangladesh, a study conducted with 251 patients looked at the association of socio-economic status and Body Mass Index with the quality of life after mastectomy at National Institute of Cancer Research Hospital (NICRH) and found significant deterioration of physical and emotional well-being, and cognitive status of patients etc. The study also found that patients with lower body mass index had lower scores in the emotional well-being assessment, particularly among the younger group of patients (Rahman, Ahsan, Monalisa, & Rahman, 2014) . Another study in Bangladesh found that participants were worried over the burden on family and obligations to complete household chores and child rearing (Ahmad, Kabir, Purno, Islam, & Ginsburg, 2017).

Aside from body image and isolation from their social networks including families and friends, there were fears of death and rejection in the breast cancer patients. A quantitative descriptive study done in a Nigerian teaching hospital with 63 clinic attendees found various kinds of fear associated with breast cancer such as, fear of death and fear about negative reaction from people, which were matter of concern for the study respondents (Ohaeri, Ofi, & Campbell, 2012). Another quantitative semi-structured survey conducted with 33 young (mean age 37 years) African American breast cancer survivors in the USA reveal that breast cancer treatment interfered with employment and it negatively hampered romantic relationships. Moreover, women needed additional emotional support during and after diagnosis (Lewis, Sheng, Rhodes, Jackson, & Schover, 2012). Another cross-sectional study conducted among 118 women with breast cancer in the city of Ahvaz in Iran found that nearly 70% of the participants had death anxiety which affected them both physically and mentally (Karampour, Fereidooni-Moghadam, Zarea, & Cheraghian, 2018).

In addition to emotional and social attributes of having breast cancer on the survivors, there are cultural attributes that factor into the psychosocial aspects of the patients. A study conducted among 102 breast cancer survivors from different ethnicities (African American, Asian American, Latina and Caucasian) in the USA, researchers have found that cultural beliefs were prevalent in Asian American women which may deter them from accessing psychosocial care. They were identified as being disinclined to discuss emotional problems and feelings about breast cancer with strangers (Ashing-Giwa et al., 2004). Religion and spirituality are very important aspects of Asian American women’s experiences with breast cancer. They hold a strong belief on power of prayer, and some may place more importance on spirituality than on treatment and health care providers (Ashing-Giwa et al., 2004). In Pakistan, 13% of 200 women (median age 35 years) surveyed in a quantitative study were found to have cultural and social fears that having breast cancer may bring disgrace to their families; 4% believed that it might lead to rejection by their spouses or divorce leading them to depression and trauma (Raza, Sajun, & Selhorst, 2012).

c. Impact on gender, body-image and relationships

As discussed in the previous section, some studies report the worry over loss of breast and weight loss. The cause behind this worry is due to the impact of relationship that is brought by breast cancer and consequent treatments, especially mastectomy. Breasts are considered to be part of women’s physical beauty, loss of a breast can create a lot of distress where women themselves feel less of a “woman” inside (Vaziri & Lotfi Kashani, 2012). In 1997, a case control study in USA compared 864 breast cancer survivors with age matched controls looked at sexual health problems associated with breast cancer. The study concluded that there was no change in the sexual functions among the breast cancer survivors and their healthy counterparts. However, some problems regarding sexual function such as sexual interest, communication and affection in partner were reported by those receiving chemotherapy leading to depression and trauma (Ganz et al., 1998). In a study conducted in the USA among cancer survivors, the researchers found that many women expressed negative feelings about their bodies after their cancer surgeries. In particular they report feelings of inadequacy, loss of self-confidence and self-worth, unhappiness and depression (Ashing-Giwa et al., 2004). Similarly other studies conducted with European, American and Latin ethnic women in USA found body image and sexual problems being immediately reported following diagnosis of breast cancer (Fobair et al., 2006). In a study with 34 participants conducted in Australia, the participants expressed a great concern with body image after being diagnosed with cancer. The participants explained that being malnourished from the disease and treatment, they felt unattractive, and were concerned over the loss of breast and hair (Beatty, Oxlad, Koczwara, & Wade, 2008). A study done among 281 couples who have been diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer in USA found significant sexual problems and gaps in communication in the couple due to breast cancer (Milbury & Badr, 2012). Another literature review published in 2012 stated in their finding that feeling of loss of femininity and sexual attractiveness can be common after mastectomy (Vaziri & Lotfi Kashani, 2012). Participants at the Young Survival Coalition Research Think Tank Meeting in 2015 urged future research to identify the psychosocial problems and design effective measures to prevent and manage negative psychosocial outcomes. (Korde et al., 2015).

The specific psychosocial concerns of Nigerian women with breast cancer include feeling of loss of femininity, fear of inability to breastfeed, decreased sexual activity and loss of affection from the husband (Ohaeri, Campbell, Ilesanmi, & Ohaeri, 1999; Adesunkami, Lawal, Adebusola, & Durosimi, 2006; Odigie, Tanaka, Yusufu, Dawotola & Margaritoni, 2009). South Asian women were found to suffer from guilt, shame and self-reproach from not being able to fulfill their familial duties reported by a systematic review in 2014. All these were identified as stressor which evolves from gender role expectations (Bedi & deVins, 2016). In Bangladesh, studies investigating the impact of breast cancer on gender dynamics and relationships was not available.

SECTION V – STIGMA AND MISCONCEPTION RELATED TO BREAST CANCER

This section shares a review of various misconceptions regarding the stigma around the disease, its occurrence as well as those associated with screening and treatment options as described in the literature.

Stigma around cancer itself

Due to the lack of understanding around causation of cancer, women have many misconceptions around cancer. From a study conducted among 102 breast cancer survivors in the United States, it was found that some women believed that cancer is contagious, breast trauma or the use of wired bras will lead to breast cancer, or that breast cancer almost always results in loss of breasts (Ashing-Giwa et al., 2004). A qualitative study conducted in United Kingdom among 24 women of South Asian origin found that some women believed that cancer was contagious, and it could be caused by carelessly using the word “cancer” (Karbani et al., 2011). A review of literature on Sub-Saharan Africa found that breast cancer causation was conceptualized to be linked with supernatural powers, which may influence their decision of health seeking and lead them to seek alternative ways of treatment rather than going to the doctor (Tetteh & Faulkner, 2016). A report by middle east based newspaper The National stated that breast cancer related stigma among the middle-eastern population also include effect of breast cancer on women’s self-esteem, their relationships with spouses and other family members, abandonment by families etc. (The National, 2016).

Similarly such misconceptions have emerged in South Asia. In a comprehensive multi country literature review conducted in 2014 focused on South Asia, which explored the cultural considerations of breast cancer among South Asians that showed breast cancer for woman in South Asia is a taboo and the topic is not discussed openly within the community (Bedi & Devins, 2016). Another qualitative exploratory study conducted from 2012-2014 in Bengaluru India revealed that diagnosis of cancer is invariably linked with stigma. Women reported fear of cancer transmission; personal blame for somehow being contracted with the disease; fear of the inevitability of disability and death with a cancer diagnosis were three main drivers of stigma associated with breast cancer. The study also found that the stigma is manifested as isolation and/or verbal abuse by the people in the community because they think it was her fault/ punishment for evil deed. Women in the study were reported to hide their diagnosis and physical manifestations, may not seek treatment on time or rarely adhere to treatment suggested (Nyblade, Stockton, Travasso, & Krishnan, 2017). All these stigmatization can lead to seclusion and social withdrawal of the breast cancer patients. For example, a qualitative study with 52 breast cancer patients in Mumbai, India between 1991-early 2000 reported 20% of women did not disclose their diagnosis even to close friends due to fear of stigmatization (Ramanakumar, Balakrishna, & Ramarao 2005).

Stigma around breast cancer screening and treatment

Just like stigmas and misconceptions around breast cancer, there are also stigma and misconception associated with breast cancer screening and treatment. A qualitative study looking at breast cancer experience of 34 Asian American women in USA during 2003 found that there was a general lack of awareness regarding benefits of screening among these women. The study also found that the women preferred not to discuss the psychosocial aspects of breast cancer or seek care for psychosocial effects, rather they were more likely to seek peace of mind through religious activities such as prayers etc. (Tam Ashing, Padilla, Tejero, & Kagawa-Singer, 2003). It has also been reported by another USA based study that Asian American women have less knowledge about their own bodies and about the benefits of screening and early detection (Ashing-Giwa et al., 2004). A review of literature from sub-saharan countries found that Sudanes women also have stigma around screening due to their faith and their practice of covering up their bodies (Tetteh & Faulkner, 2016). A review of literature on perceived health related stigma from breast cancer concluded that this can have negative consequences on the quality of life with breast cancer patients (Wang, Bai, Lu, & Zhang, 2017). Stigma can cause the breast cancer patients to opt for traditional medicine rather than proper treatment. For example, in Nigeria, it was found that patients were most likely to first visit Christian religious faith healers and traditional medicine healers before visiting hospitals regardless of level of education attained. This link with faith healers were found to be maintained even when western biomedical treatment was on-going at hospitals. (Ohaeri Campbell, Ilesanmi, & Ohaeri, 1999).

Stigma and misconceptions around screening is also present in south Asian women. A recent study conducted in India with 134 patients aged 44-60 years, who received surgical treatment for breast cancer found significant association between stigma and opting for breast conservative surgery rather than mastectomy (Tripathi et al., 2017). The study also found stigma is associated with level of education of the patients (Tripathi, Datta, Agrawal, Chatterjee, & Ahmed, 2017). These findings from India suggest that there are strong links between stigma and breast cancer treatment that can impact the survival and treatment outcome for breast cancer patients.

Similarly, in rural Bangladesh, myths about causes of breast cancer are reported, for example, the patient committing “evil deeds” or sins according to religious guidelines and as a punishment, receiving such disease from God. Traditional medicine and traditional healers (providers) are also a trusted option for the treatment of breast cancer among Bangladeshi women. However it can cause significant delay in seeking treatment. A cross sectional study investigating the impact of using alternative medicine for breast cancer in Bangladesh, recruited 200 breast cancer patients randomly from NICRH and showed that nearly half of the respondents sought help from alternative medicine such as unani, ayurvedic, homeopathy or folk medicine at first. Preference to use homeopathy treatment (86.02%) was highest among all modes of alternative medicine (Akhtar, Akhtar, & Rahman, 2018). However, this study reports higher prevalence of preferring treatment though alternative or traditional medicine can negatively impact care seeking for breast cancer. Akhter et al. found that first resort to alternative medicine resulted in a mean patient delay of 4 months for cancer treatment (Akhtar, Akhtar, & Rahman, 2018). Among Bangladeshi women, there are also assumptions of high cost, even though low-cost or free breast treatment and health services are available (Story, Love, Salim, Roberto, Krieger, & Ginsburg, 2012). All these myths are known to hinder or delay care seeking for symptoms.

Stigma around male breast cancer

Similarly men also have stigma associated with bodies when facing breast cancer. According to United Breast Cancer Foundation, a non-profit organization for breast cancer based in New York, USA, highlight how breast cancer month and the whole breast cancer awareness campaign seemingly ostracizes men. The author although acknowledges the justified focus on women because of the staggering high incidence among women, also points to the need for inclusive space to talk about male breast cancer. The author also stresses on the fatality being quite high given the incidence among men (“Male Breast Cancer: The Stigma,” 2016). A recent qualitative study conducted in Canada with 15 male breast cancer patients found that, stigma starts from the diagnosis and extends through screening, treatment and rehabilitation. The respondents of the study noted that it was unmanly to have breast cancer, since “Men do not have breasts” and to describe their disease, they would rather describe it as cancer of chest than breast cancer. The respondents also mentioned that experience of breast mammogram as well as experience in the waiting room were both stigmatizing for the men because mammogram is seen as a woman’s test (Skop, Lorentz, Jassi, Vesprini, & Einstein, 2018). A mixed methods study from April 2016 – March 2018 on male breast cancer patients in Germany aimed to identify the types of stigma that they feel and the ways in which it can be reduced. The study found that male breast cancer patients felt stigmatized by both the cancer care system as well as the female patients seeking cancer care. Stigma was also found to be more during rehabilitation compared to treatment phase (chemotherapy, radiation, follow-up survey) or within family (Midding et al., 2018).

SECTION VI – CONCLUSIONS

This review on breast cancer aimed to understand the current state of the disease in Bangladesh and other LMICs and HICs, explore the related causes and treatment options, and examine the consequences and related stigma and misconceptions. However, further research is needed to know the accurate national prevalence of breast cancer in Bangladesh, which can give a clear assimilation of this disease in the country and encourage greater employment of screening and treatment procedures at large. For example, if the accuracy of the disease occurrence is known for the country, policies and health systems reform to devise effective and population level screening procedures that can help avert the adverse consequences patients face through early screening and reduce the huge burden on the health system of expensive treatment options. The 4th sector program, Health Population Nutrition Sector Programme (HPNSP) 2017 – 2022, identified the importance of controlling non-communicable diseases specifically cancer diseases in order to achieve universal health coverage and sustainable development goals (SDGs) with a broader lens, specific focus on breast cancer screening at different tiers of the health system is included in the priority action areas along with promoting healthy and active lifestyles that are key to breast cancer prevention. Mass awareness, campaigns, advocacy through multisectoral collaborations are also included in the priority agenda of the Government of Bangladesh. Alongside females, males should also be included in the target population for mass campaigns and awareness generation activities for prevention of breast cancer. In conclusion, the reviewers recommend continuous efforts and enabling environment for research around breast cancer to generate concrete evidence and anticipate successful implementation of the 4th HPNSP 2017–2022 priority action agendas to combat breast cancer in Bangladesh.

Challenges and limitations

There is a lack of peer reviewed journal articles on mental health and family impact of breast cancer, the disease and related consequences, as well as facts and figures, exploring patients or population level views on the disease in Bangladesh. In total only 18 articles were found on breast cancer in Bangladesh that covers mostly biomedical causation, treatment and screening aspects of the disease. The reviewers hence also reviewed news related to breast cancer experts’ opinion published in local newspapers (both Bengali and English) in the last one year.

References:

1. a2i. (2017). Seminar on Breast Cancer Awareness. Last accessed: feb 9, 2019: https://a2i.gov.bd/seminar-on-breast-cancer-awareness/

2. Adesunkami, A. R., Lawal, O. O., Adebusola, K., & Durosimi, M. A. (2006). The severity, outcome and challenges of breast cancer in Nigeria. Breast,15(3):399–409.

3. Ahmad, F., Kabir, S. F., Purno, N. H., Islam, S., & Ginsburg, O. (2017). A study with Bangladeshi women: Seeking care for breast health. Health Care for Women International, 38(4), 334–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2016.1263305

4. Ahmed, K., Asaduzzaman, S., Bashar, M. I., Hossain, G., & Bhuiyan, T. (2015). Association Assessment among Risk Factors and Breast Cancer in a Low Income Country: Bangladesh. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention : APJCP, 16(17), 7507–7512. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26625753

5. Akhtar, K., Akhtar, K., & Rahman, M. M. (2018). Use of Alternative Medicine Is Delaying Health-Seeking Behavior by Bangladeshi Breast Cancer Patients. European Journal of Breast Health, 14(3), 166–172. https://doi.org/10.5152/ejbh.2018.3929

6. American Cancer Society. (2017). Treatment of Breast Cancer by Stage. Retrieved February 11, 2019, from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/breast-cancer/treatment/treatment-of-breast-cancer-by-stage.html

7. Ark, M., Lemons, C., Aul, P., & Oss, G. (2001). ESTROGEN AND THE RISK OF BREAST CANCER. J Med. Retrieved from http://www.nejm.org

8. Ashing-Giwa, K. T., Padilla, G., Tejero, J., Kraemer, J. Wright, K., Coscarelli, A., Clayton, S., Williams, I., & Hills, D. (2004). Understanding The Breast Cancer Experience of Women: A Qualitative Study Of African American, Asian American, Latina And Caucasian Cancer Survivors Psychooncology, 13(6): 408–428.

9. Beatty, L., Oxlad, M., Koczwara B., & Wade, T. D., (2008). The psychosocial concerns and needs of women recently diagnosed with breast cancer: a qualitative study of patient, nurse and volunteer perspectives. Health Expectations, 11:331–342

10. Bedi, M, & Devins, G. M. (2016). Cultural considerations for South Asian women with breast cancer. J Cancer Surviv 10 :31–50. doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0449-8

11. Befort, C. A., & Klemp, J. (2011). Sequelae of Breast Cancer and the Influence of Menopausal Status at Diagnosis Among Rural Breast Cancer Survivors. Journal of Women’s Health, 20(9), 1307–1313. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2010.2308

12. British Council. (n.d.). Bangladesh fight against breast cancer through campaigns. Last accessed: Feb 9, 2019. https://www.britishcouncil.org.bd/en/active-citizens-bangladesh-fight-against-breast-cancer-through-campaigns

13. Canadian Cancer Society. (2012). Breast cancer statistics at a glance http://www.cancer.ca/Canada-wide/About%20cancer/Cancer%2 20statistics/Stats%20at%20a%20glance/Breast%20cancer.aspx?sc_lang=en. Accessed 2 Jan 2013.

14. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). What Is Breast Cancer? Retrieved February 10, 2019, from https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/basic_info/what-is-breast-cancer.htm

15. Chandan, M. S. K. (2019, January 11). A Fatal Diagnosis: Cancer treatment in Bangladesh | The Daily Star. The Daily Star. Retrieved from https://www.thedailystar.net/star-weekend/spotlight/news/losing-the-war-cancer-1685734

16. Chowdhury, T. I., Love, R. R., Chowdhury, M. T. I., Artif, A. S., Ahsan, H., Mamun, A., … Salim, R. (2015). Feasibility Study of Case-Finding for Breast Cancer by Community Health Workers in Rural Bangladesh. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention : APJCP, 16(17), 7853–7857. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26625810

17. Danaei, G., Vander Hoorn, S., Lopez, A. D., Murray, C. J., & Ezzati, M. (2005). Causes of cancer in the world: comparative risk assessment of nine behavioural and environmental risk factors. The Lancet, 366(9499), 1784–1793. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67725-2

18. de Koning, H. J., Martin van Ineveld, B., van Oortmarssen, G. J., de Haes, J. C. J. M., Collette, H. J. A., Hendriks, J. H. C. L., & van der Maas, P. J. (1991). Breast cancer screening and cost-effectiveness; Policy alternatives, quality of life considerations and the possible impact of uncertain factors. International Journal of Cancer, 49(4), 531–537. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.2910490410

19. De Silva, S., Tennekoon, K. H., Karunanayake, E. H., Amarasinghe, I., & Angunawela, P. (2014). Analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 large genomic rearrangements in Sri Lankan familial breast cancer patients and at risk individuals. BMC research notes, 7(1), 344.

20. Million Women Study Collaborators (2005). Endometrial cancer and hormone-replacement therapy in the Million Women Study. The Lancet, 365(9470), 1543–1551. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66455-0

21. Engel, L. S., Satagopan, J., Sima, C. S., Orlow, I., Mujumdar, U., Coble, J., … Alavanja, M. C. (2014). Sun Exposure, Vitamin D Receptor Genetic Variants, and Risk of Breast Cancer in the Agricultural Health Study. Environmental Health Perspectives, 122(2), 165–171. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1206274

22. Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C. (2014) GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC Cancer- Base No. 11. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer. Available from http://globocan.iarc.fr accessed on 07.07.14.

23. Fighting the stigma around breast cancer – The National. (2016, March 31). The National, p. Editorial. Retrieved from https://www.thenational.ae/opinion/fighting-the-stigma-around-breast-cancer-1.155216

24. Fiorica, J. V. (2016). Breast Cancer Screening, Mammography, and Other Modalities. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology, 59(4):688-709.

25. Fobair, P., Stewart, S. L., Chang, S., D’Onofrio, C., Banks, P. J., & Bloom, J. R. (2006). Body image and sexual problems in young women with breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 15(7), 579–594. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.991

26. Friedenreich, C. M., & Cust, A. E. (2008). Physical activity and breast cancer risk: impact of timing, type and dose of activity and population subgroup effects. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 42(8), 636–647. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2006.029132

27. Fu, R., Chang, M. M., Chen, M., & Rohde, C. H. (2017). A Qualitative Study of Breast Reconstruction Decision-Making among Asian Immigrant Women Living in the United States. Plast Reconstr Surg. 139(2):360-368. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000002947

28. Gangane, N., Khairkar, P., Hurtig, A. K., & San Sebastián, M. (2017). Quality of Life Determinants in Breast Cancer Patients in Central Rural India. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP, 18(12), 3325.

29. Ganz, P. A., Greendale, G. A., Petersen, L., Kahn, B. B., & Bower, J. E. (2003). Breast cancer in younger women: reproductive and late health effects of treatment. Undefined. Retrieved from https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Breast-cancer-in-younger-women%3A-reproductive-and-of-Ganz-Greendale/6341c558cba792900de3346eb9fa189c88f1b777

30. Ganz, P. A., Rowland, J. H., Desmond, K., Meyerowitz, B. E., & Wyatt, G. E. (1998). Life after breast cancer: understanding women’s health-related quality of life and sexual functioning. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 16(2), 501–514. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.501

31. Ginsberg, G. M., Lauer, J. A., Zelle, S., Baeten, S., & Baltussen, R. (2012). Cost effectiveness of strategies to combat breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer in sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia: mathematical modelling study. BMJ, 344(mar02 2), e614–e614. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e614

32. Ginsburg, O. M., Chowdhury, M., Wu, W., Chowdhury, M. T. I., Pal, B. C., Hasan, R., … Salim, R. (2014). An mHealth model to increase clinic attendance for breast symptoms in rural Bangladesh: can bridging the digital divide help close the cancer divide? The Oncologist, 19(2), 177–185. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0314

33. Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration, G. B. of D. C., Fitzmaurice, C., Allen, C., Barber, R. M., Barregard, L., Bhutta, Z. A., … Naghavi, M. (2017). Global, Regional, and National Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived With Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life-years for 32 Cancer Groups, 1990 to 2015: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Oncology, 3(4), 524–548. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5688

34. Hoare, T., Thomas, C., Biggs, A., Booth, M., Bradley, S., & Friedman, E. (1994). Can the uptake of breast screening by Asian women be increased? A randomized controlled trial of a linkworker intervention. Journal of Public Health Medicine, 16(2), 179–185. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7946492

35. Hoskins, C. N. (1997). Breast cancer treatment-related patterns in side effects, psychological distress, and perceived health status. Oncology Nursing Forum, 24(9), 1575–1583. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9348598

36. Hossain, M. S., Ferdous, S., & Karim-Kos, H. E. (2014). Breast cancer in South Asia: A Bangladeshi perspective. Cancer Epidemiology, 38(5), 465–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2014.08.004

37. Howlader, N., Noone, A., Krapcho, M., Miller, D., Bishop, K., Kosary, C., … Cronin, K. (Eds.). (2017). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2014 (April). Bethseda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Retrieved from https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2014/

38. Hussain, S. A., & Sullivan, R. (2013). Cancer control in Bangladesh. Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology, 43(12), 1159–1169. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyt140

39. International Agency for Research on Cancer. (2016). Breast Cancer Screening: IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention Volume 15 (Vol. 15). Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsr1504363

40. International Agency for Research on Cancer. (2018a). Fact Sheet on Breast Cancer. Retrieved from http://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/20-Breast-fact-sheet.pdf

41. International Agency for Research on Cancer. (2018b). Global Cancer Observatory. Retrieved February 9, 2019, from http://gco.iarc.fr/

42. Iqbal, J., Ferdousy, T., Dipi, R., Salim, R., Wu, W., Narod, S. A., … Ginsburg, O. (2015). Risk Factors for Premenopausal Breast Cancer in Bangladesh. International Journal of Breast Cancer, 2015, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/612042

43. Islam, R. M., Bell, R. J., Billah, B., Hossain, M. B., & Davis, S. R. (2016). Awareness of breast cancer and barriers to breast screening uptake in Bangladesh: A population based survey. Maturitas, 84, 68–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.11.002

44. Islam, R. M., Billah, B., Hossain, M. N., & Oldroyd, J. (2017). Barriers to Cervical Cancer and Breast Cancer Screening Uptake in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention : APJCP, 18(7), 1751–1763. https://doi.org/10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.7.1751

45. Karampour, S., Fereidooni-Moghadam, M., Zarea, K., & Cheraghian, B. (2018). The prevalence of death anxiety among patients with breast cancer. BMJ supportive & palliative care, 8(1), 61-63.

46. Kelsey, J. L., Gammon, M. D., & John, E. M. (1993). Reproductive factors and breast cancer. Epidemiologic Reviews, 15(1), 36–47. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8405211

47. Khan, F., Ahmad, N., & Biswas, F. N. (2018). Cluster Analysis of Symptoms of Bangladeshi Women with Breast Cancer. Indian Journal of Palliative Care, 24(4), 397–401. https://doi.org/10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_77_18

48. Koopman, C., Nouriani, B., Erickson, V., Anupindi, R., Butler, L. D., Bachmann, M. H., … Spiegel, D. (n.d.). Sleep Disturbances in Women With Metastatic Breast Cancer. Retrieved from https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/73246/j.1524-4741.2002.08606.x.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

49. Korde, L. A., Partridge, A. H., Esser, M., Lewis, S., Simha, J., & Johnson, R,. H.(2015). Breast Cancer in Young Women: Research Priorities. A Report of the Young Survival Coalition Research Think Tank Meeting. JOURNAL OF ADOLESCENT AND YOUNG ADULT ONCOLOGY 4(1). doi: 10.1089/jayao.2014.0049

50. Kuchenbaecker, K. B., Hopper, J. L., Barnes, D. R., Phillips, K.-A., Mooij, T. M., Roos-Blom, M.-J., … Olsson, H. (2017). Risks of Breast, Ovarian, and Contralateral Breast Cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers. JAMA, 317(23), 2402. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.7112

51. Lauby-Secretan, B., Scoccianti, C., Loomis, D., Benbrahim-Tallaa, L., Bouvard, V., Bianchini, F., & Straif, K. (2015). Breast-Cancer Screening — Viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. New England Journal of Medicine, 372(24), 2353–2358. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsr1504363

52. Lewis, P. E., Sheng, M., Rhodes, M. M., Jackson, K. E., & Schover, L. R. (2012). Psychosocial Concerns of Young African American Breast Cancer Survivors. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 30(2), 168–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2011.651259

53. Lin, N. U., Bellon, J. R., & Winer, E. P. (2004). CNS metastases in breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology : Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 22(17), 3608–3617. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2004.01.175

54. Male Breast Cancer: The Stigma. (2016). Retrieved February 18, 2019, from http://ubcf.org/male-breast-cancer-stigma-sexist/

55. Mathew, A., Gajalakshmi, V., Rajan, B., Kanimozhi, V., Brennan, P., Mathew, B. S., & Boffetta, P. (2008). Anthropometric factors and breast cancer risk among urban and rural women in South India: a multicentric case–control study. British journal of cancer, 99(1), 207.

56. Mccormack, V. A., Dos, I., & Silva, S. (2006). Breast Density and Parenchymal Patterns as Markers of Breast Cancer Risk: A Meta-analysis. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0034

57. Midding, E., Halbach, S. M., Kowalski, C., Weber, R., Würstlein, R., & Ernstmann, N. (2018). Men With a “Woman’s Disease”: Stigmatization of Male Breast Cancer Patients-A Mixed Methods Analysis. American Journal of Men’s Health, 12(6), 2194–2207. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988318799025

58. Milbury, K., & Badr, H. (2012). Sexual problems, communication patterns, and depressive symptoms in couples coping with metastatic breast cancer. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3079

59. Mock, V., Dow, K. H., Meares, C. J., Grimm, P. M., Dienemann, J. A., Haisfield-Wolfe, M. E., … Gage, I. (1997). Effects of exercise on fatigue, physical functioning, and emotional distress during radiation therapy for breast cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 24(6), 991–1000. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9243585

60. Mushlin, A. I., & Fintor, L. (1992). Is screening for breast cancer cost‐effective? Cancer, 69(S7), 1957–1962. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19920401)69:7+<1957::AID-CNCR2820691716>3.0.CO;2-T

61. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. (2018). NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) Breast Cancer (3.2018). National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Retrieved from http://www.nccn.org/patients

62. NHS. (2016). Breast cancer in women – Treatment – NHS. Retrieved February 11, 2019, from https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/breast-cancer/treatment/

63. Nyblade, L., Stockton, M., Travasso, S., & Krishnan, S. (2017). A qualitative exploration of cervical and breast cancer stigma in Karnataka, India. BMC Women’s Health, 17(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-017-0407-x

64. Odigie, V. I., Tanaka. R., Yusufu, L. M. D., Dawotola D. A, & Margaritoni, M. (2009) Psychosocial effects of mastectomy on married African women in Northwestern Nigeria. Psycho-Oncology, 19(8):893-7 doi:10.1002/pon.1675

65. Oeffinger, K. C., Fontham, E. T. H., Etzioni, R., Herzig, A., Michaelson, J. S., Shih, Y.-C. T., … Wender, R. (2015). Breast Cancer Screening for Women at Average Risk. JAMA, 314(15), 1599. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.12783

66. Ohaeri, B. M., Ofi, A. B., & Campbell, O. B. (2012). Relationship of knowledge of psychosocial issues about cancer with psychic distress and adjustment among breast cancer clinic attendees in a Nigerian teaching hospital. Psycho-Oncology, 21(4), 419–426. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1914

Ohaeri, J.U., Campbell, O.B., Ilesanmi, A., Ohaeri, B. M. (1999). The opinion of caregivers of some women with breast cancer on some aspects of the disease. West Afr J Med, 18(1):6–12

67. Okonkwo, Q. L., Draisma, G., der Kinderen, A., Brown, M. L., & de Koning, H. J. (2008). Breast Cancer Screening Policies in Developing Countries: A Cost-effectiveness Analysis for India. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 100(18), 1290–1300. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djn292

68. Palesh, O. G., Collie, K., Batiuchok, D., Tilston, J., Koopman, C., Perlis, M. L., … Spiegel, D. (2007). A longitudinal study of depression, pain, and stress as predictors of sleep disturbance among women with metastatic breast cancer. Biological Psychology, 75(1), 37–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BIOPSYCHO.2006.11.002

69. Park, H. S., Kim, J. H., Lee, D. W., Song, S. Y., Park, S., Kim, S. Il, … Cho, Y. U. (2018). Gasless Robot-Assisted Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy: A Case Report. Journal of Breast Cancer, 21(3), 334–338. https://doi.org/10.4048/jbc.2018.21.e45

70. Park, J.-H., Bae, S. H., Jung, Y. S., & Kim, K. S. (2012). Quality of Life and Symptom Experience in Breast Cancer Survivors After Participating in a Psychoeducational Support Program. Cancer Nursing, 35(1), E34–E41. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e318218266a